We returned home to a spread of delicious sushi. Awaiting us was Hisako’s mother and father, of course, as well as her sister, Atsumi-San, and her sister’s husband, Kesuke-San.

We returned home to a spread of delicious sushi. Awaiting us was Hisako’s mother and father, of course, as well as her sister, Atsumi-San, and her sister’s husband, Kesuke-San.

We exchanged introductions, and devoured copious quantities of sushi.

Due to the excellent management of Naoko-San, the veggie-friendly and non-veggie-friendly sushi were carefully separated onto two platters, just for me. The homemade veggie sushi rolls tasted exquisite.

In addition to sushi, we also each indulged in a bowl of hot soba noodles, the consumption of which marks one of the many unique New Year’s traditions in Japan.

Atsumi-San, or A-Chyan, as the family calls her, had studied English a little bit in school, and though somewhat short of what I would call fluent, she was able to say quite a few things in English, and was happy to help me improve my caveman Japanese.

A-Chyan and I of course also exchanged gifts, or omiyage, as per the Japanese custom. Before departing for Japan, I had acquired a lovely Japanese-made tea tin adorned with a floral paper print, and in it had ensconced a couple ounces of my favorite herbal tea, bourbon vanilla rooibos.

I had acquired this gift expressly based on Hisako’s intel which indicated rooibos to be her sister’s favorite tea as well.

In exchange, A-Chyan bequeathed unto me a miniature Osechi-Ryori decoration, complete with a pair of tiny “ebi,” or “shrimp,” featuring little black eyes—adorable!

Osechi-Ryori, for those not familiar with the term, is a special type of Japanese bento made for, and eaten exclusively on, the first day of the new year, and which is always presented in beautiful lacquer boxes.

Each of the foods included in Osechi-Ryori has a special significance, no doubt derived from ancient Shinto stories. For example the “ebi” is eaten to ensure a long life—literally until your back becomes curved like a shrimp! As this was New Year’s Eve, we wouldn’t be eating life-sized Osechi-Ryori until the following day.

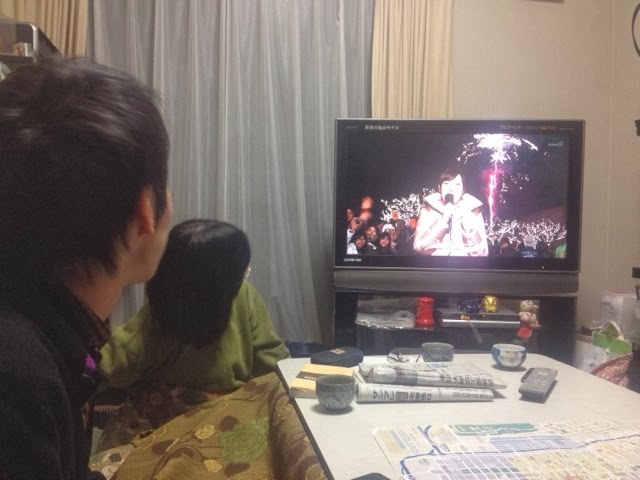

Watching the progress toward the new year on T.V., we discussed the many differences between Japanese and American New Year’s festivities.

In Japan, most families send off the old year by going to the temples, where bells are rung one-hundred and eight times by people selected at random from the crowd. Apparently this practice frees those present from the one-hundred and eight desires described in Japanese Buddhist teachings.

Once midnight descends, everyone proceeds directly to the shrines to welcome in the new year with hot sake, sweet black beans, fortune telling, and a whole array of other pagan rituals.

In the Yamada family, for reasons which The Princess has been unable to fully explain, her family watches the first portion of these festivities on the “telebee,” gathered of course around the unspeakably glorious kotatsu, and then, come midnight, wanders to the local shrine to exchange the prior year’s talisman for the new one, and to acquire good luck for the coming year.

As midnight struck, we grabbed our warmest clothing, and prepared to depart. Donning my thermal underlayer in the back room, I could hear the deep, round tones of a distant temple bell ringing out the one-hundred and eight note death knell of the fading year.

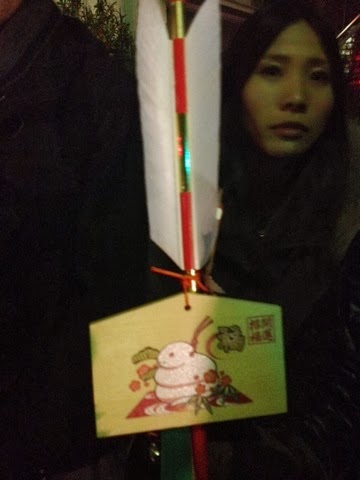

Hisako’s sister, Atsumi-San (pictured here with Kesuke-San), was elected to carry the 2013 talisman to the local shrine, where it would be scheduled for destruction, and replaced with the 2014 model.

To ensure optimum blessings of the gods, such New Year’s talismans are kept in the entryways of Japanese homes throughout the twelvemonth.

This year’s is the Horse, while last year’s was the Snake.

Together, we scampered into the cold of night, setting out on a journey to beseech blessings from the gods. Reaching the main street, we found dozens of others thronging, just like us, toward the shrine.

In the short time it took us to reach our destination, the dozens gave way to hundreds.

The shrine itself glowed against the midnight winter sky, its Torii gate and long vertical banners lit up with light, alive with the sounds of people.

As we neared the perimeter of the shrine, we encountered small booths selling hot tempura, croquettes, and other tantalizing delicacies.

Within the holy grounds, just to the left of the main walkway, stood a large booth-sized receptacle, ready to receive the discarded talismans of the prior year. Koji-San approached this holy totem-dumpster with notable nonchalance, and into it cast the Yamada Family’s 2013 talisman.

Unlike in the West, where so many of our ceremonies are conducted with the utmost of gravity, in Japan the temples alone remain reserved for somber events, while the shrines stand ready for those of joy.

Here at the shrine, all is a festival—people talk and eat snacks purchased from the nearby booths, while children happily throw their family talismans into the holy dumpster, laughing all the while.

Over the coming days, Koji informed me, the talismans would be burned at the shrine, releasing in their ashes any bad luck remaining from the old year.

During the week leading up to this moment, people have been cleaning their homes, offices, and even cars, to prepare for a fresh start to the new year.

Nowhere on Earth is the “new” portion of “New Year’s” taken so seriously as in Japan.

We passed by statues of vicious-looking “Komainu,” or pairs of guardian kami who protect the shrine (similar in many respects to Western gargoyles), and proceeded to the ritual hand washing fountain.

Left, right, sip, spit—and BAM! Ready once again to greet the gods!

As I returned the long-handled bamboo cup to the fountain, I momentarily pondered over how much spit must actually be contained in the dirty water receptacle areas at these stations.

How many Olympic swimming pools could be filled were it all collected from the entirety of Japan?

Lacking the instruments necessary to acquire any conclusive data, we instead joined the press as it approached the steps of the shrine.

Upon individuals, and upon groups, the priests of the shrine were busily bestowing the annual good luck blessings.

Such ceremonies conducted at Shinto shrines generally involve an acolyte equipped with a decorative bit of white paper, cut so as to resemble leaves, and attached to the end of a stick, which the holy personage then waves over the heads of his or her supplicants.

These leaf-like arrangements of white paper, which I came to think of as holy Shinto confetti, can also be seen hanging up as decorations in shrines across the country.

The Princess and I went together to receive our blessing, a huge line of people awaiting their turn behind us.

We each tossed a five-yen coin into the donation box, bowed twice, claped twice, and bowed once more as a priestess waved the holy confetti over our heads, uttering the while an archaic Japanese prayer which I was entirely unable to comprehend.

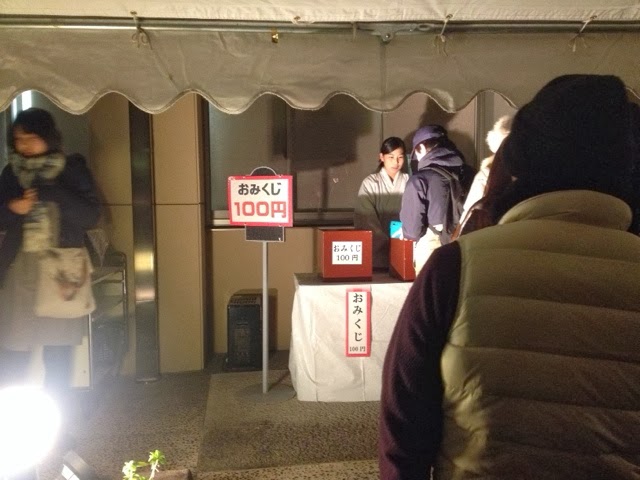

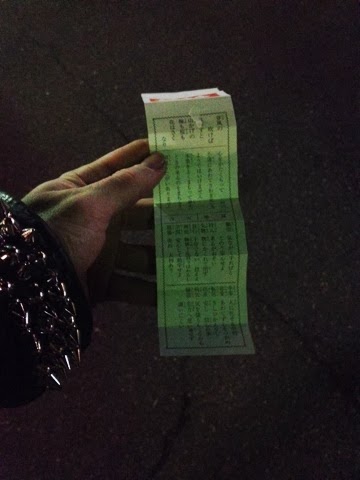

With this accomplished, we migrated toward the fortunes and lucky charms section of the bustling shrine. For a mere one-hundred yen each, we took turns reaching into a fortune-box to draw out our Shinto luck-forecast for the coming year.

The Princess drew one which she described as “maa maa,” or “so so,” but mine, as it so happened, is apparently supposed to be the very best of all. No matter what I set out to accomplish this year, it seems I will have the blessings of the Shinto gods on my side.

[Insert long evil laugh here.]

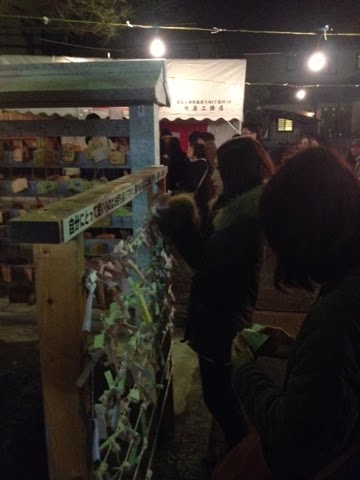

For those who received less favorable forecasts than us, there was a special area where folks could attach their fortune-prediction papers in hopes of having their contents rectified by the gods.

Apparently A-Chyan’s fortune was closer to the shittier side of the Torii, so to speak, and thus she attached it, alongside many others, to the special offering spot. Apparently not everyone gets to be among the Okami Elect.

Nearby, I noticed they were selling a half-beverage, half-soup concoction made of black beans, and decided to give it a go. Apparently my fortune is already working at full bore, for the contents of the cup were warm, sweet, and delectable. Lucky me!

With our refreshed talisman, we returned home. A-Chyan and Kesuke-San departed for their home, while The Princess and I, along with her mother and father, climbed into our beds, happy with the fresh beginning of the new year.

Yet for The Princess and I, our slumbers were doomed to be short lived, for in a few hours we would be meeting three of Hisako’s best friends for a climb up Mt. Misen on the Island of Miyajima, where we would witness Amaterasu Oomikami herself, the Shinto Goddess of the Sun—greatest among the deities of Japan—on her first ascent into the heavens of the new year.

Related

0 comments on “Oyasumi, 2013” Add yours →